What's Good for the Goose is Good for the GANder: A Look into Generative Adversarial Networks for Neural Language Generation

Recently, I took this course on Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Deep Learning. I learned a lot about different types of neural networks and how they are applied to language models in things we use to communicate every day (i.e. web search, ads, emails, language translation).

For the final project, my project partner and I thought it would be interesting to tackle neural text generation. Generating authentic human language is a significant and worthwhile challenge in Natural Language Processing (NLP); it has wide-ranging applications from neural machine translation to text summarization to dialogue generation.

The standard methodology for text generation has been statistical token generation using recurrent neural netowrks (RNNs) with long short-term memory (LSTM) cells via maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), i.e. maximize the conditional probability of the next token based on the training data. However, there are several shortcomings to this approach. One is exposure bias: during generation, the generator may see partial sequences it has not seen in training. Another is that it tends to produce boring and statistically-safe predictions, unlike traditional human text. This has actually insprired several projects aimed at generating text indistinguishable from human text, such as the Turing test. This also naturally leads us to the idea of a 2-part model: a generator and a discriminator that simply judges whether a given sentence was human-generated.

What is a GAN?

GANs have mostly been used in computer vision, for generating photorealistic images or reconstructing images based on a provided sample set of images. For instance, this video of a horse-turned-zebra was created using a GAN. There are also other cool applications of GANs, such as neural style transfer: this is a fairly well-known mapping of the artistic style of The Starry Night painting onto photographs.

More formally, a GAN is a generative model for unsupervised machine learning, which is used to extract or describe latent structure in unlabeled data.

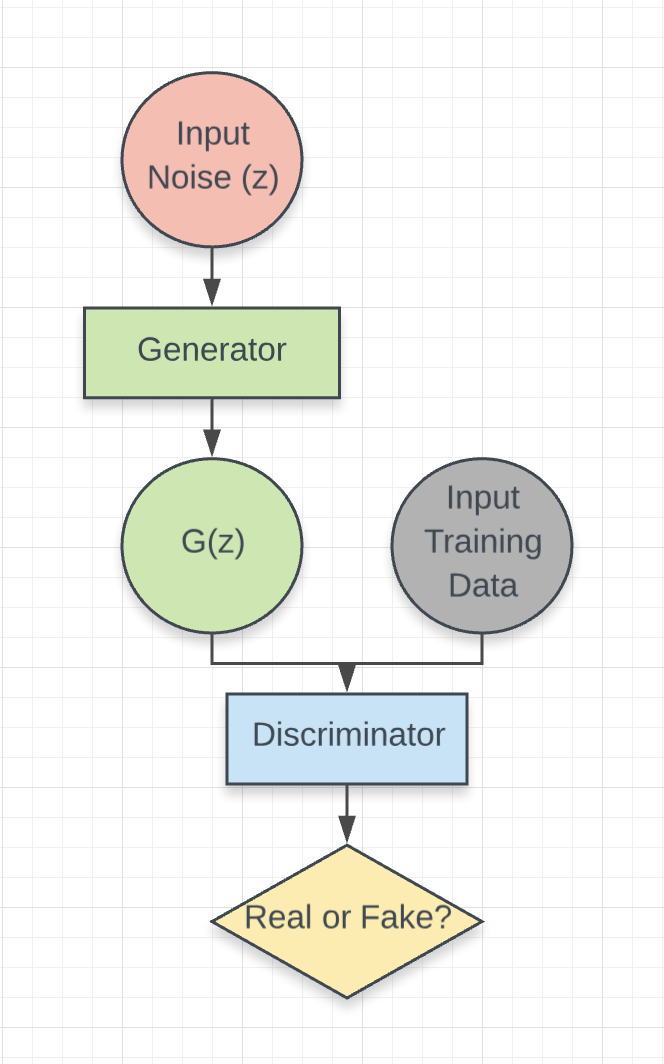

A GAN is actually made up of 2 different neural networks, each of which has its own distinct inputs and outputs:

- Discriminator: A traditional classification network that discriminates its inputs as real (a part of the training data) or fake (generated samples that are not a part of the training data).

- Generator: A neural network that generates samples that are similar to the training data. In other words, it takes some “random noise” as input, then transforms this “noise” into an output that is similar in structure to the data of the desired model we are trying to “learn.”

Together, we say that the goal of the generator is to “fool” the discriminator into thinking that the desired output it produces is “real,” while the discriminator tries to correctly classify this generated data as real (not generated) or fake (generated). We connect these two networks into a constant feedback loop, competing against each other in a zero-sum game.

Figure 1. Generator-Discriminator building blocks of Generative Adversarial Network

Given multilayer perceptrons (generator) and (discriminator), as well as input training data and noise variables , we model this as a minimax game:

Simultaneously, we train to maximize the probability of assigning the correct labels (“real” or “fake”) to training data and generated samples, and to minimize the probability that assigns the correct labels. (This concept was first introduced in the paper Goodfellow et al. 2014)

How does this work in practice?

Realistically, however, we recall that log loss increases as our predicted probability diverges from the true label, and decreases when the opposite occurs. This implies that at the start of the game, when the generator is poor, the discriminator will easily differentiate between “fake” and “real” inputs; as a result, the gradient for our generator will be small and saturates. This means our will never update. It makes sense, therefore, to separate the cost function for to maximize rather than minimizing .

Additionally, in practice, it is impossible to optimize completely before training , as this would result in overfitting the discriminator to our input data. Instead, we maintain a near-optimal solution for at all times by optimizing much slower than we do . We implement this iteratively, applying simultaneous gradient descent to both and by alternating steps of optimizing with a single step of optimizing .

Some Limitations of GAN Applications to NLP

Even though GANs have been pretty successful in computer vision for generating images, they have often failed in natural language tasks. Why is this?

In image generation, gradients are back-propagated from the result of the discriminator through the start of the generator to update both models at the same time. This is possible because images are composed of continuous pixel values. However, in the case of text data, generated words are represented as discrete numerical indices, and it is impossible to slightly adjust the value of word with a gradient. (Imagine backpropagating gradients through discrete numerical indices {1: ‘cat’, 2: ‘dog’}. What word would index 1.0000008 represent?)

Instead, we must implement a reinforcement strategy, using “rewards” from the discriminator to update the generator’s parameters so that we maintain our discrete distribution. Recent publications have applied GANs to discrete data with promising results: